It’s a while since I wrote a blog post, but recently I discovered a story so uplifting I was inspired to restart. Alice Herz-Sommer was born in Prague in 1903, one of five children, including a twin sister. Her childhood was intellectually stimulating: her parents ran a cultural salon and visitors included Franz Kafka, Gustav Mahler, and Sigmund Freud. At the age of six she started learning piano and by her teens was teaching and performing. She met Leopold Somner, a violinist, in 1931 and married him two weeks later. They led a busy and creative life and had one son, Raphael.

After the Nazi invasion of Czechoslovakia, most of Alice’s family emigrated to Palestine but Alice remained to care for her sick mother, Sophie. In 1942, Sophie was arrested and later killed. Alice channeled her grief into her piano playing, practicing endlessly until her own arrest, together with Leopold and Raphael, in 1943. They were sent to Terezin-Theresienstadt camp where Alice’s musical prowess became her saviour. She later told of her experience:

‘We had to play because the Red Cross came three times a year. The Germans wanted to show its representatives that the situation of the Jews in Theresienstadt was good. Whenever I knew that I had a concert, I was happy. Music is magic. We performed in the council hall before an audience of 150 old, hopeless, sick and hungry people. They lived for the music. It was like food to them. If they hadn’t come, they would have died long before. As we would have.’

In the years of her incarceration, she played more than 150 concerts. Raphael also performed in the children’s opera staged by the Nazis to show ‘normal’ life in the camps. Sadly, Alice was separated from her husband and he died in Dachau, six days before the end of the war.

After the war, Alice moved to Palestine and was reunited with her twin, though many of her family, her husband’s family and all her friends had died. But what makes Alice’s story exceptional is she didn’t let this tragedy define her, instead living a fulfilling life. She once said: ‘I am looking for the nice things in life. I know about the bad things, but I look only for the good things.’

In 1962, she attended the Eichmann trial in Jerusalem, commenting: ‘I have to say that I had pity for him. I have pity for the entire German people. They are wonderful people, no worse than others.’

She taught music before moving to London in 1986, to support Raphael in his career as a cellist. Sadly, Raphael died of a heart attack in 2001, aged 64, a devastating blow, but Alice remained positive. She lived alone and for many years had an active daily routine that included swimming, playing the piano for three hours and attending classes at the University of the Third Age.

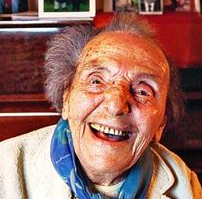

Alice became the oldest Holocaust survivor and died in 2014, aged 110. She attributed her long life to optimism: ‘I was always ugly. My twin sister was very beautiful. But she was a pessimist and so she died at 74. If you are a pessimist the whole organism is in a tension all the time.’ When asked whether she was afraid of dying, she replied: ‘Not at all. No. I was a good person, I helped people, I was loved, I have a good feeling.’